A renowned Indian architect and educator on Wednesday was named the first architect from his country to win the field’s highest honor, the Pritzker Architecture Prize, which is bestowed by Chicago’s billionaire Pritzker family.

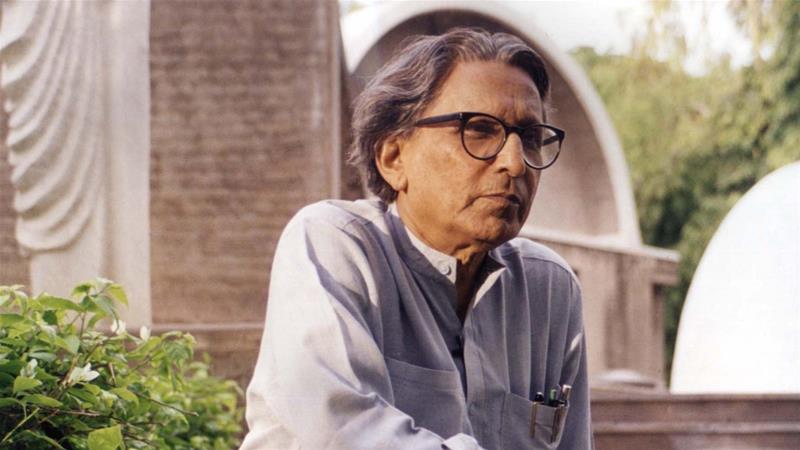

Little known in the U.S., 90-year-old Balkrishna Doshi has won a global reputation in architectural circles for designs that transform the universal language and robust materials of 20th century modernists Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn, for whom he worked, into buildings rooted in local sensibilities and circumstances.

Doshi “constantly demonstrates that all good architecture and urban planning must not only unite purpose and structure but must take into account climate, site, technique, and craft, along with a deep understanding and appreciation of the context,” the nine-member jury that awards the prize said in its citation.

The jurors also praised Doshi for creating “an architecture that is serious, never flashy or a follower of trends.”

First presented in 1979, the Pritzker Prize is given annually to recognize “consistent and significant contributions to humanity and the built environment through the art of architecture.” In light of Doshi’s age, it is the equivalent of a lifetime achievement award. Like previous winners, he will receive $100,000 and a bronze medallion. The award will b[full_width][/full_width]e presented in Toronto in May.

With more than 100 buildings to his credit, Doshi is known for dealing creatively with conditions in his country, the world’s second-most populous, which is infamous for its overcrowded slums.

His projects include a low-income housing development that is said to effectively accommodate 80,000 people in a network of houses, courtyards and internal pathways. His design studio consists of a cluster of buildings, some with vaulted roofs, that are enlivened by grassy terraces and reflecting ponds. The jury singled out his Indian Institute of Management in Bangalore, which was built from 1977 to 1992, saying the architect “has created spaces to protect from the sun, catch the breezes and provide comfort and enjoyment in and around the buildings.”

The architect is equally well-known for shaping dialogue about his field. He founded and directed the School of Architecture and Planning in Ahmedabad, which was renamed CEPT University in 2002. His numerous overseas teaching posts include a visiting professorship at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

In an interview in Ahmedabad, INDIA,

Interviewer: What inspires you? Which artists or works of art inspired you?

Balkrishna Doshi: Life [chuckles]. There are many. I am inspired by India’s cities and towns where I travelled a lot, like Benares, south Indian temples [and] the old parts of the city of Ahmedabad.

One of the most inspiring monuments that have had an impact on me is Fatehpur Sikri in northern India.

The works of great architects, in Europe and America, also inspire me.

Interviewer: What does architecture mean to you?

Doshi: Celebrating life. When you are in a good space, a beautiful space, maybe near a water fountain, you become aware of the shadows casting strange images.

There is a sudden consciousness, propelled by beautiful spaces, where you are aware of your inner feelings – that’s when we feel happy and we create.

I think architecture is a backdrop to life.

Interviewer: In a previous public lecture, you have referred to the Hindu philosophy of Leela or creation. Could you expand on that?

Doshi: The focus, while creating, is to enhance the subtle nuances of experiences. We breathe in and out but external stimuli make us shocked, surprised, aroused.

We are not always aware of the skin of our body. But if you are in a space where your senses are heightened, it touches your inner core. That’s what temples do, that’s what mosques do, that’s what grand palaces do.

I have always tried to create images through activities. That’s what architects do.

You will be surprised how our experiences differ as shadows change. The sun and the moon and the breeze breathe life into buildings. Architecture makes you aware of your senses.

Interviewer: You are known for pioneering low-cost housing. The Aranya Low-Cost Housing project you designed is capable of accommodating more than 80,000 people. Why did you prioritise social housing?

Doshi: I used to walk in the streets of Mumbai in the 1950s. I saw the streets at night full of migrants from across the country, sleeping on the pavements. The image of their night life on the streets is indelible. I thought to myself: Isn’t this part of India? Are they not my people?

I was determined then that one day I will work for this “other half” and show how people can live, how we can build for these people.

What, after all, is the role of an architect? Is he supposed to build only monuments? Is he supposed to work only for clients? Is social consciousness not part of the architect’s duty?

That’s what I took as my challenge.

Interviewer: Tell us a bit about your childhood and when your interest in architecture began.

Doshi: Since childhood, while going through day-to-day activities like playing on the streets, walking to the market, meeting people, I realised that life means gathering, rejoicing.

Work happens in between. I studied outside in the [open] spaces, not in the classroom.

When I was an eight- or nine-year-old boy, I used to visit my grandfather’s furniture workshop. I was aware of structures and spaces.

Later, I became involved in urban planning and industrial townships.

I feel architects are not conscious of their social responsibility. We see buildings as a product.

We make a building as a transaction between myself and the client and my skill. But this is not the right approach.

So I thought of setting up a school where good architects will be nurtured.

Also, I continued with my passion for working in low-cost housing.

Interviewer: What would you say defines modern architecture?

Doshi: I would use the word contemporary. If I am staying in a mud house but using a mobile phone, would that be modern or old? These are nomenclatures but everything we do is contemporary.

For me, modern architecture is both today and tomorrow because it is continuously used and is workable.

Interviewer: What is the significance of this award?

Doshi: This award means a lot to me. It is so overwhelming. It’s a great honour for me and India.

This award has many ramifications. I was thinking, maybe with the Pritzker Architecture Prize now, India and Indian professionals, practitioners and architecture schools will become more hopeful.

It’s encouragement to work passionately; it’s another mode of joy and recognition. If this award spurs others to emulate the architectural spirit, that would be great.

This award also encourages me for other reasons: how it will trigger the imagination, how it will help in creating a diverse mind.

I am hopeful the [Indian] government will start looking at architecture in a different light. Even [Indian] developers might start thinking on these lines.

The last American architect to win the Pritzker was Thom Mayne, of Los Angeles, who won in 2005. A Chicago architect has never won the prize.

If you liked our post please leave a comment below and share.